In ring theory, a branch of abstract algebra, a quotient ring, also known as factor ring, difference ring or residue class ring, is a construction quite similar to the quotient group in group theory and to the quotient space in linear algebra. It is a specific example of a quotient, as viewed from the general setting of universal algebra. Starting with a ring and a two-sided ideal in , a new ring, the quotient ring , is constructed, whose elements are the cosets of in subject to special and operations. (Quotient ring notation always uses a fraction slash "".)

Quotient rings are distinct from the so-called "quotient field", or field of fractions, of an integral domain as well as from the more general "rings of quotients" obtained by localization.

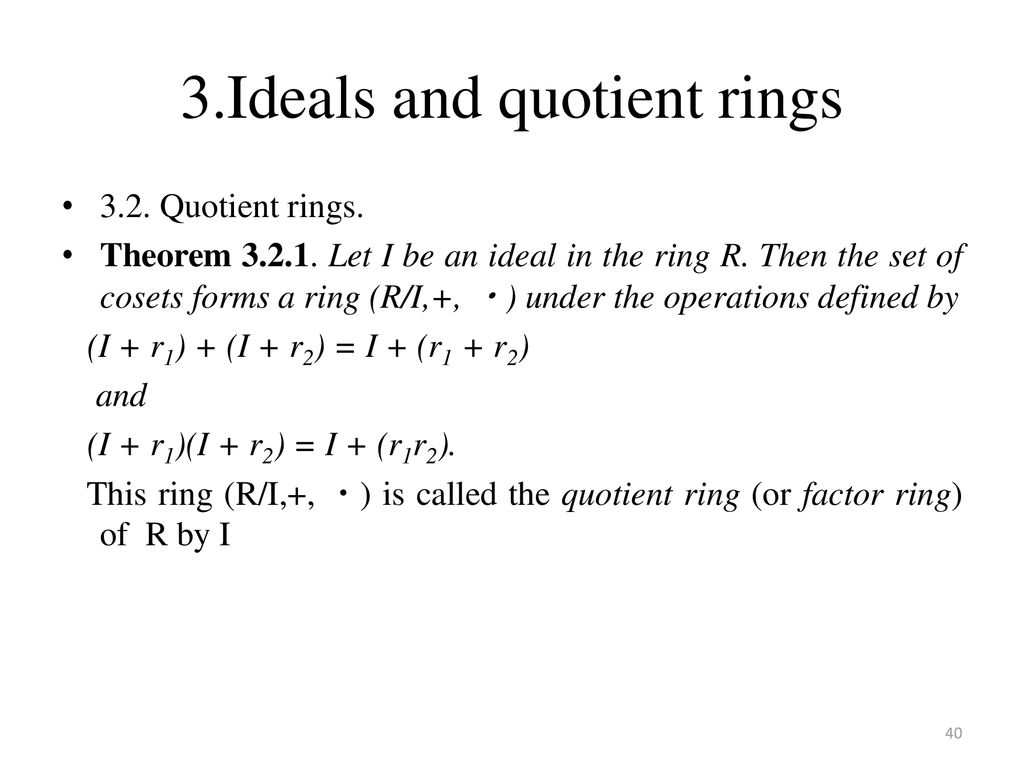

Formal quotient ring construction

Given a ring and a two-sided ideal in , we may define an equivalence relation on as follows:

- if and only if is in .

Using the ideal properties, it is not difficult to check that is a congruence relation. In case , we say that and are congruent modulo (for example, and are congruent modulo as their difference is an element of the ideal , the even integers). The equivalence class of the element in is given by:

This equivalence class is also sometimes written as and called the "residue class of modulo ".

The set of all such equivalence classes is denoted by ; it becomes a ring, the factor ring or quotient ring of modulo , if one defines

- ;

- .

(Here one has to check that these definitions are well-defined. Compare coset and quotient group.) The zero-element of is , and the multiplicative identity is .

The map from to defined by is a surjective ring homomorphism, sometimes called the natural quotient map or the canonical homomorphism.

Examples

- The quotient ring is naturally isomorphic to , and is the zero ring , since, by our definition, for any , we have that , which equals itself. This fits with the rule of thumb that the larger the ideal , the smaller the quotient ring . If is a proper ideal of , i.e., , then is not the zero ring.

- Consider the ring of integers and the ideal of even numbers, denoted by . Then the quotient ring has only two elements, the coset consisting of the even numbers and the coset consisting of the odd numbers; applying the definition, , where is the ideal of even numbers. It is naturally isomorphic to the finite field with two elements, . Intuitively: if you think of all the even numbers as , then every integer is either (if it is even) or (if it is odd and therefore differs from an even number by ). Modular arithmetic is essentially arithmetic in the quotient ring (which has elements).

- Now consider the ring of polynomials in the variable with real coefficients, , and the ideal consisting of all multiples of the polynomial . The quotient ring is naturally isomorphic to the field of complex numbers , with the class playing the role of the imaginary unit . The reason is that we "forced" , i.e. , which is the defining property of . Since any integer exponent of must be either or , that means all possible polynomials essentially simplify to the form . (To clarify, the quotient ring is actually naturally isomorphic to the field of all linear polynomials , where the operations are performed modulo . In return, we have , and this is matching to the imaginary unit in the isomorphic field of complex numbers.)

- Generalizing the previous example, quotient rings are often used to construct field extensions. Suppose is some field and is an irreducible polynomial in . Then is a field whose minimal polynomial over is , which contains as well as an element .

- One important instance of the previous example is the construction of the finite fields. Consider for instance the field with three elements. The polynomial is irreducible over (since it has no root), and we can construct the quotient ring . This is a field with elements, denoted by . The other finite fields can be constructed in a similar fashion.

- The coordinate rings of algebraic varieties are important examples of quotient rings in algebraic geometry. As a simple case, consider the real variety as a subset of the real plane . The ring of real-valued polynomial functions defined on can be identified with the quotient ring , and this is the coordinate ring of . The variety is now investigated by studying its coordinate ring.

- Suppose is a -manifold, and is a point of . Consider the ring of all -functions defined on and let be the ideal in consisting of those functions which are identically zero in some neighborhood of (where may depend on ). Then the quotient ring is the ring of germs of -functions on at .

- Consider the ring of finite elements of a hyperreal field . It consists of all hyperreal numbers differing from a standard real by an infinitesimal amount, or equivalently: of all hyperreal numbers for which a standard integer with exists. The set of all infinitesimal numbers in , together with , is an ideal in , and the quotient ring is isomorphic to the real numbers . The isomorphism is induced by associating to every element of the standard part of , i.e. the unique real number that differs from by an infinitesimal. In fact, one obtains the same result, namely , if one starts with the ring of finite hyperrationals (i.e. ratio of a pair of hyperintegers), see construction of the real numbers.

Variations of complex planes

The quotients , , and are all isomorphic to and gain little interest at first. But note that is called the dual number plane in geometric algebra. It consists only of linear binomials as "remainders" after reducing an element of by . This variation of a complex plane arises as a subalgebra whenever the algebra contains a real line and a nilpotent.

Furthermore, the ring quotient does split into and , so this ring is often viewed as the direct sum . Nevertheless, a variation on complex numbers is suggested by as a root of , compared to as root of . This plane of split-complex numbers normalizes the direct sum by providing a basis for 2-space where the identity of the algebra is at unit distance from the zero. With this basis a unit hyperbola may be compared to the unit circle of the ordinary complex plane.

Quaternions and variations

Suppose and are two non-commuting indeterminates and form the free algebra . Then Hamilton's quaternions of 1843 can be cast as:

If is substituted for , then one obtains the ring of split-quaternions. The anti-commutative property implies that has as its square:

Substituting minus for plus in both the quadratic binomials also results in split-quaternions.

The three types of biquaternions can also be written as quotients by use of the free algebra with three indeterminates and constructing appropriate ideals.

Properties

Clearly, if is a commutative ring, then so is ; the converse, however, is not true in general.

The natural quotient map has as its kernel; since the kernel of every ring homomorphism is a two-sided ideal, we can state that two-sided ideals are precisely the kernels of ring homomorphisms.

The intimate relationship between ring homomorphisms, kernels and quotient rings can be summarized as follows: the ring homomorphisms defined on are essentially the same as the ring homomorphisms defined on that vanish (i.e. are zero) on . More precisely, given a two-sided ideal in and a ring homomorphism whose kernel contains , there exists precisely one ring homomorphism with (where is the natural quotient map). The map here is given by the well-defined rule for all in . Indeed, this universal property can be used to define quotient rings and their natural quotient maps.

As a consequence of the above, one obtains the fundamental statement: every ring homomorphism induces a ring isomorphism between the quotient ring and the image . (See also: Fundamental theorem on homomorphisms.)

The ideals of and are closely related: the natural quotient map provides a bijection between the two-sided ideals of that contain and the two-sided ideals of (the same is true for left and for right ideals). This relationship between two-sided ideal extends to a relationship between the corresponding quotient rings: if is a two-sided ideal in that contains , and we write for the corresponding ideal in (i.e. ), the quotient rings and are naturally isomorphic via the (well-defined) mapping .

The following facts prove useful in commutative algebra and algebraic geometry: for commutative, is a field if and only if is a maximal ideal, while is an integral domain if and only if is a prime ideal. A number of similar statements relate properties of the ideal to properties of the quotient ring .

The Chinese remainder theorem states that, if the ideal is the intersection (or equivalently, the product) of pairwise coprime ideals , then the quotient ring is isomorphic to the product of the quotient rings .

For algebras over a ring

An associative algebra over a commutative ring is a ring itself. If is an ideal in (closed under -multiplication), then inherits the structure of an algebra over and is the quotient algebra.

See also

- Associated graded ring

- Residue field

- Goldie's theorem

- Quotient module

Notes

Further references

- F. Kasch (1978) Moduln und Ringe, translated by DAR Wallace (1982) Modules and Rings, Academic Press, page 33.

- Neal H. McCoy (1948) Rings and Ideals, §13 Residue class rings, page 61, Carus Mathematical Monographs #8, Mathematical Association of America.

- Joseph Rotman (1998). Galois Theory (2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 21–23. ISBN 0-387-98541-7.

- B.L. van der Waerden (1970) Algebra, translated by Fred Blum and John R Schulenberger, Frederick Ungar Publishing, New York. See Chapter 3.5, "Ideals. Residue Class Rings", pp. 47–51.

External links

- "Quotient ring", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Ideals and factor rings from John Beachy's Abstract Algebra Online

![21. let a denote the quotient ring [x]/(x*). then (a) there are exactly](https://cdn.eduncle.com/library/scoop-files/2022/10/can_image_1665668442201.jpg)